California Loses Another Wine Pioneer

[ad_1]

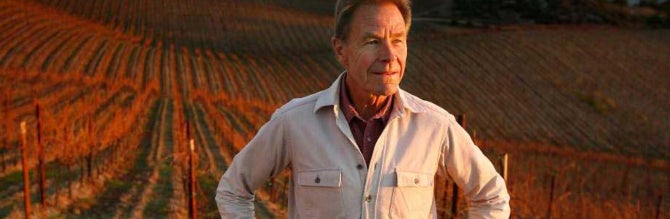

Mount Harlan Pinot Noir superstar Josh Jensen has died, aged 78.

© Calera

| Josh Jensen saw the potential for Mount Harlan to make great Pinot Noir.

Josh Jensen, who convinced even Burgundians that California can make great Pinot Noir, died in his sleep on Saturday at age 78.

The founder of Calera winery, Jensen came along a bit later than most of the California wine industry’s modern-era pioneers, but he belongs in that group. His focus on single-vineyard Pinot Noirs, made the same way in order to highlight the impact of terroir, set a template that is so commonplace today that it’s easy to forget that almost all of Jensen’s peers would have blended all of their grapes together.

Jensen’s wines were interesting, and so was he. His father was a dentist but not a wine drinker, despite the efforts of his fellow dentist George Selleck, who introduced young Josh to fine wine. Jensen studied history at Yale; then went to Oxford to study anthropology. The six-foot-four California native was in the Guinness Book of World Records as the heaviest man (at 214 pounds) to row in the 1967 Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race.

To the end of his life, Jensen was an adventurer. He died after a bad case of Covid that exacerbated a case of pneumonia he contracted while climbing Mt. Kiliminjaro. He loved cycling and became part of an international group of cyclist-aesthetes with vintners Dominique Lafon, Christophe Roumier, Egon Müller and Jean-Pierre Perrin; the group followed each day of hard biking with a night of gourmet consumption.

While at Oxford, Jensen decided Burgundy where was where his wine interest lay. He worked the grape harvest in 1970 at Domaine Romanée-Conti; he later worked a harvest at Domaine Dujac. He made good use of the DRC connection throughout his career; there was a rumor that he jumped over a fence to snip some cuttings that he brought back to the US in a suitcase. Jensen always gave a Mona Lisa smile when asked about the “suitcase clones”.

A fact is that there is now a Calera clone of Pinot Noir, based on cuttings Jensen got from fellow Pinot pioneers at Chalone Vineyard. Jensen propagated it and made it available to nurseries and the clone is now planted statewide.

The good dirt

Burgundians are obsessed with soil; Jensen became similarly obsessed with finding limestone in California, using Bureau of Mines geological maps. The 324-acre site he eventually found on Mount Harlan is so remote that there was no road, not to mention no electricity or water. On the plus side, in 1974, Jensen bought what has become one of the great Pinot Noir vineyards in the world for just $18,000.

His first vintage, in 1978, was just 65 cases. But already he had marked out three different vineyards, called Jensen, Selleck and Reed. He believed the wine from them would taste different, and he was right. Calera Selleck is fruit-driven, Calera Reed is earthy and spicy (Calera’s current winemaker Mike Waller calls it “the hippie chick”) and Calera Jensen is smooth and rich.

All of his wines were made in a way that seemed minimalist in the 1980s: only native yeast, unfiltered, with un-destemmed whole clusters. The wines were meant to age, like Burgundy; Jensen made the wines the way he thought they should be and assumed a market would develop for them.

Jensen is arguably bigger in Japan than in the US – in 2014 Calera sold 37 percent of its wine there – and the Calera Jensen Pinot is why. In the 1990s, the manga “Sommelier” compared it to DRC; all these years later, the wine’s reputation remains lifted.

But Calera is so much more accessible than DRC. In addition to single-vineyard Pinots, Calera made an affordable Central Coast Pinot Noir that used to be available even at Oakland As baseball games. He planted Chardonnay in the 1980s and later planted Viognier and Aligoté. In 2007 he was named Winemaker of the Year by the San Francisco Chronicle, and in 2013 he was on the cover of Wine Spectator with the headline “Pinot Pioneer”.

That said, Jensen had his ups and downs in business. In his early years at Calera, he supplemented his income by writing restaurant reviews for the San Francisco Chronicle under a psuedonym. He lost money throughout the 1980s. Then in the mid-’00s, even after the reputation of the wines had ascended, Calera lost money three years in a row and the entire staff took a pay cut.

Last year Jensen told San Benito.com that in the 1990s he threw himself a 50th birthday party in San Francisco.

“All of the people I invited got up to speak, and they all told the same story,” Jensen said. “They were sure I was going to lose my shirt with the Calera venture. These were business people I’d gone to high school and college with! They all thought I was going to go bankrupt. I just sat there shaking my head.”

Jensen has three adult children, a son and two daughters, but he couldn’t interest any of them into continuing his legacy. It’s really not surprising: Jensen was a well-dressed, urbane man, but his home on Mount Harlan was about as rural as California gets. In 2017, he gave up on trying and sold the winery to the Duckhorn Wine Company. The following year he moved to San Francisco, near his daughter Sylvie and two of his five grandchildren, with a view overlooking the bay.

“Where I lived for 40 years, I had a 360-degree view of untouched landscape,” Jensen told San Benito.com. “We buried all the lines and made a decision not to have telephone poles. There was zero water in my line of sight. Now, all I see is water!”

To join the conversation, comment on our social media channels.

[ad_2]